What is the Cuentos Project?

What is the Cuentos Project?

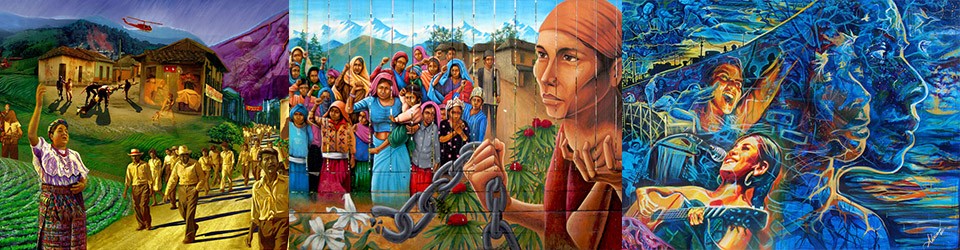

Hispanics. Latinos. Latinas. Chicanos. Chicanas. Latins. Spanish. Raza. We go by many names. And beneath this variety, there is an equally diverse set of experiences, experiences that connect Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and other parts of the Spanish-speaking hemisphere to the United States. Experiences that, together, form who we are. Lives of struggle. Lives of survival. Lives of work, of family, of progress, of hope.

Cuentos is a small attempt to record and preserve these life experiences through the practice of oral history.

People’s memories re-told in the form of oral history interviews are both precious and important. As legendary oral historian Studs Terkel wrote the practice, “I was the beneficiary of others’ generosity. My tape recorder. . . carried away valuables beyond price.” The stories of everyday people’s lives may seem unimportant or uneventful to some, including the interviewees themselves. But nothing can be further from the truth. In our stories live our hopes and dreams, our struggles and passions, our successes and failures. In our stories are our lives, our collective experiences as a people.

Why are Latino stories so important?

Based on current trends, the so-called “white majority” in the United States will be eclipsed by the non-white population in a matter of decades. Latinos will comprise a large part of this demographic shift. Even now, we are the largest “minority” population in the United States.

At the local level, the importance of the Latina/o population is even more pronounced. According to the 2010 Census, Hispanics are almost half (48.5%) of the entire population of Los Angeles County. And in San Bernardino County we are the majority at 50.5% of the total population. In many ways, Southern California is now the heart of “Latino America.”

From this perspective alone, an understanding of Latina and Latino experiences is vital to any comprehensive understanding of the United States. The people of Latin American-descent are not just a necessary part of understanding of this nation’s future. The Latina/o story is also a story whose roots in the Americas extend far back, even before the first Europeans arrived. The history of the Latina/o people in the Americas predates the founding of the US, making it older than military conquest and colonization of the present-day Southwest. And, as generations of historians have shown, Latina/Latino stories are integral parts of much of the last century of US history.

By collecting the life stories of everyday people–the memories of Latina/o history as a lived experience–the Cuentos project seeks to build a more complete understanding of our collective experience–both the stories that embody the uniqueness of our past, as well as those that illuminate the “American experience.”

Why is oral history so important?

While Latinas/os have been a part of this nation’s history for as long as it has been a nation, our experiences, thoughts, feelings, and desires have not always been part of the traditional historical record.

In fact, many of the historic conditions that have shaped the collective “Latino experience” in the United States have also made our experiences invisible with traditional historical archives. This condition of invisibility is, in many ways, shared by other populations who are traditionally poor and working class, or racially marginalized. Simply put, nonwhite populations have been historically devalued as members of the wider society, relegating their experiences to footnotes of the past.

As immigrants and the descendants of immigrants, that lack of visibility for Latinos can be measurably worse. Historic racial and economic segregation patterns have often kept Latin American immigrants away from meaningful inclusion and integration in US society. The criminalization of immigrants (and, to some extent, all “brown bodies” who fit the visible stereotype of the immigrant) has exacerbated this invisibility. And, to the extent that parts of the Latino population are only fluent in Spanish, a kind of linguistic marginalization has further underrepresented our experiences in archival records.

In this context, the act of creating a community archives of oral histories is more than an act of preserving our memories. It is an act of critical resistance to the forces of erasure. Oral histories serve to counter invisibility and the erasure it promotes by creating a community story that makes visible this condition by its very existence. Oral histories voice an alternate history to the “official record,” exposing the gaps and limits of that archive and the historians who mine it.

Well-preserved and archived oral histories prevent the ability of future generations to “not know” the history of Latina/o communities in the US. By actively filling the gaps in the historical record–and doing so on the terms of the community members themselves–oral histories not only preserve our past but do so while allowing our communities to play a role in the future story-writing and story-telling processes about them.