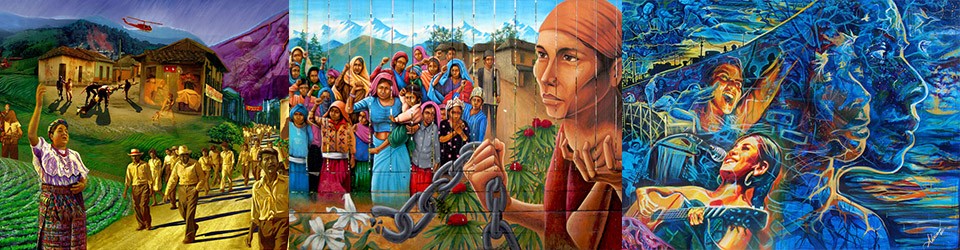

“A Hardworking People ~ Una Gente Muy Trabajadora”

“We asked for workers, but people came.”

–Max Frisch

Immigration reform has emerged as one of the most pressing issues of the early 21st century US. Though a gridlocked Congress has impeded any effort to find legislative relief for a “broken immigration system,” an amalgamation of forces–the presence of 11 million undocumented migrants; the continual desire for a cheap, flexible labor force; escalating death and militarization along the border–have combined to make immigration as central a feature of the present moment as it has been in this nation’s past.

As the nation’s largest immigrant population, Latin American immigrants often find themselves at the center of this public debate. As in decades past, however, this position has infused the Latino experience with a set of powerful contradictions. Latinos are simultaneously welcomed and forbidden in the US. Desired as a form of cheap and pliable labor, Latinos are also feared for the cultural challenge to whiteness provided by their very existence within the national borders.

As the nation’s largest immigrant population, Latin American immigrants often find themselves at the center of this public debate. As in decades past, however, this position has infused the Latino experience with a set of powerful contradictions. Latinos are simultaneously welcomed and forbidden in the US. Desired as a form of cheap and pliable labor, Latinos are also feared for the cultural challenge to whiteness provided by their very existence within the national borders.

Part of this tension rests on the widely-held belief that Latinos are a “hard-working people.” Undoubtedly, it takes very little effort to prove this maxim. Latino immigrant labor occupies the lowest rung in the US economy, often meeting the labor demands of some of the harshest jobs in the nation. US-born Latinos enjoy a better economic position than the first-generation immigrant, yet maintain a solid representation within the working-classes (and working-poor class) of the economy. Under education and underserved by the dwindling social “safety net,” Latino community survival has often nurtured a community pride in our collective sense of hard work.

While this may seem to be a favorable characteristic, depicting Latinos as workers also deprives them of other human interests and needs. For example, a 1928 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times advocated for the importation of Mexican workers to harvest California’s crops by depicting them as people biologically suited to work:

These Mexicans are accustomed to life in a semi-tropical climate. They are children of the sun, and they perform a service for which those born in colder climates are neither suited nor inclined.

This “positive stereotype,” like all stereotypes, reduces the human diversity of an entire population into one aspect of modern life. More dangerously, it can be used to explain their position within the economy as pre-determined, robbing them of the hopes and aspirations they have for a better life.

These stories are but a small sampling of that human diversity. in these stories of life, family, education, and work, we try to use oral histories with Latinos and Latinas in southern California to suggested larger understandings affecting the population as a whole.

These are stories of hope and progress, as well as struggle and marginalization. By focusing on “work” we hope to suggest the ways in which Latina/o lives both embody the “American Dream” as well as expose its limits. After all, as legendary oral historian Studs Terkel described his book Working, work is not only about progress but also about “violence–to the spirit as well as to the body.”